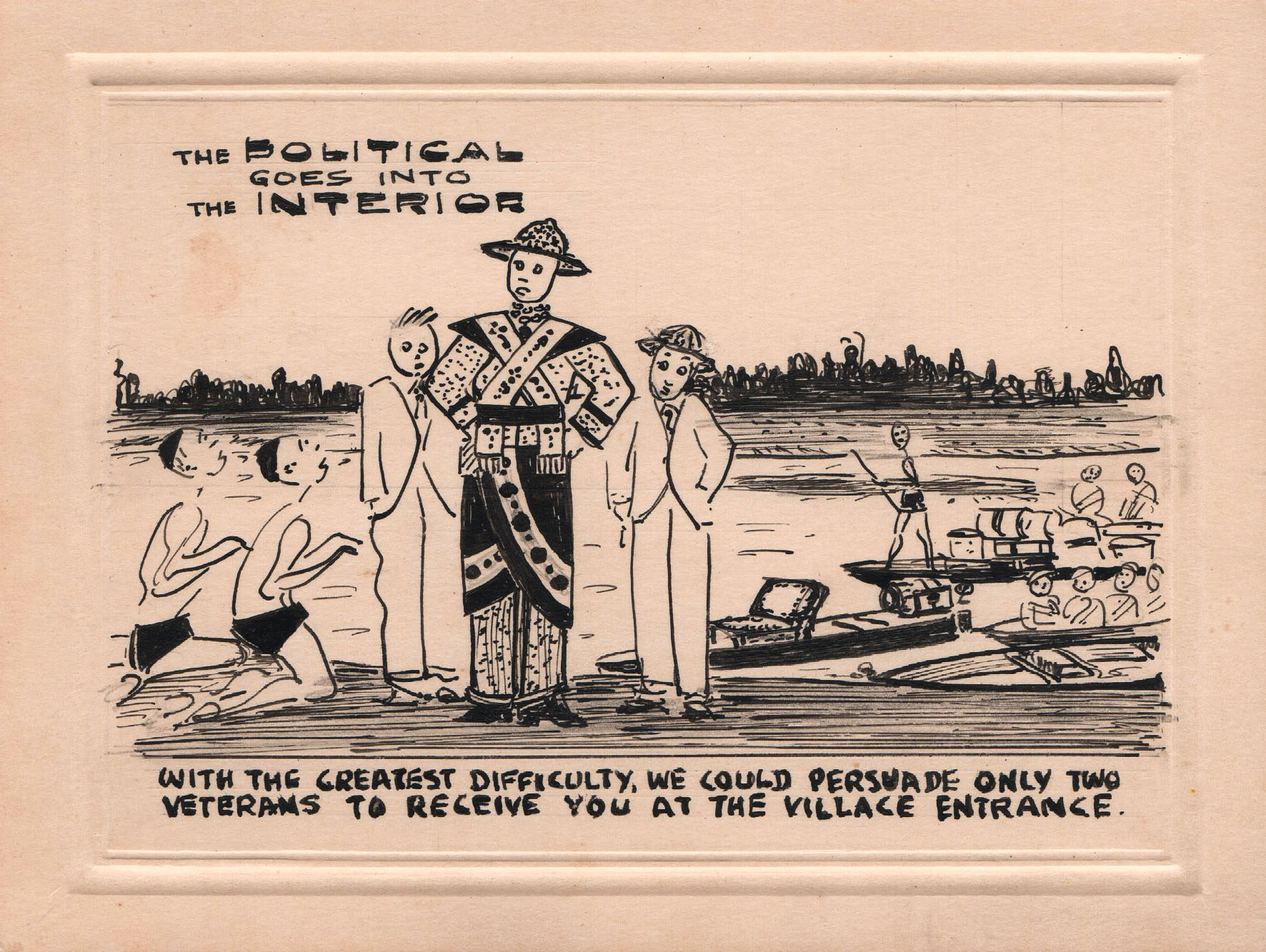

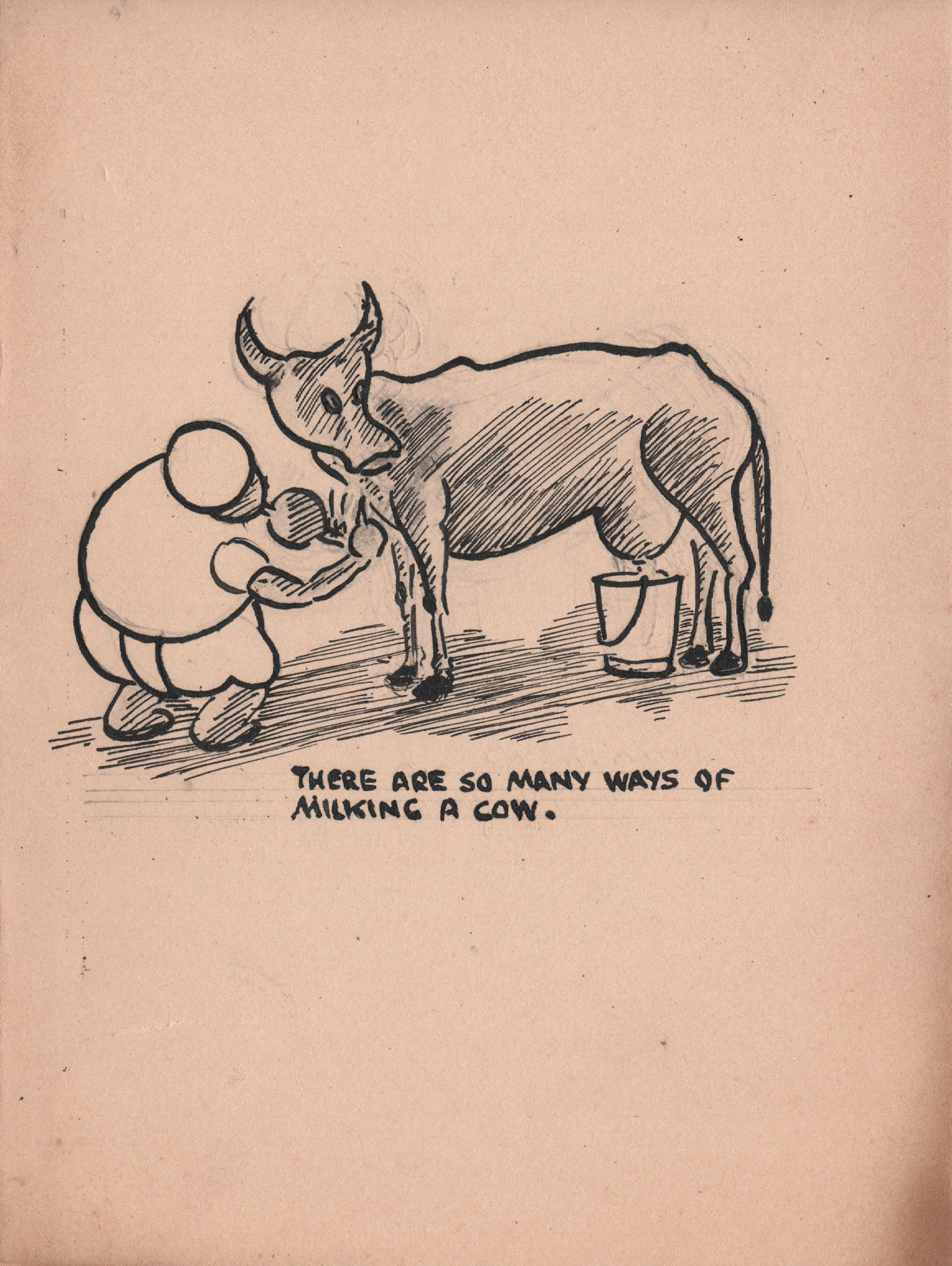

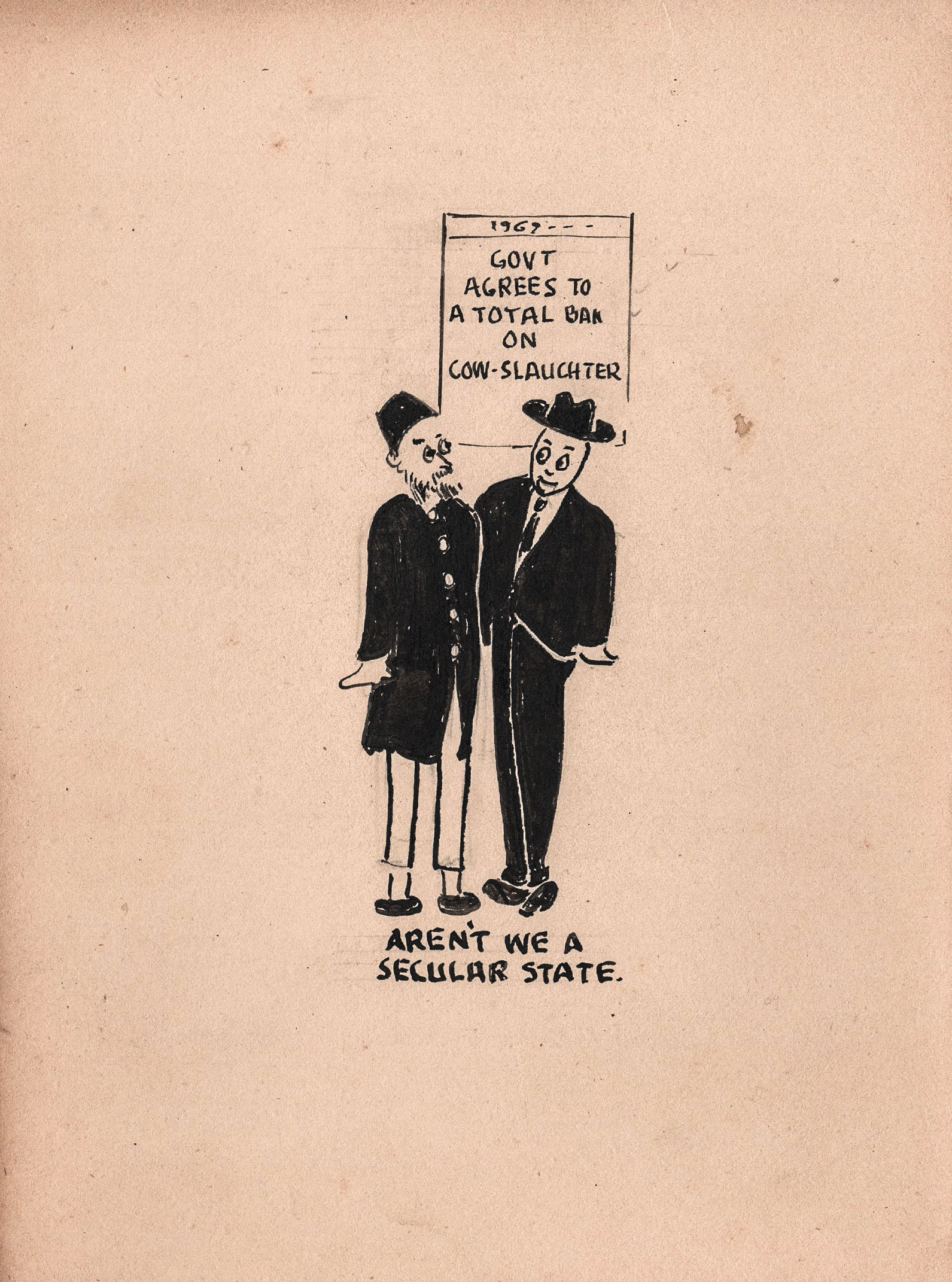

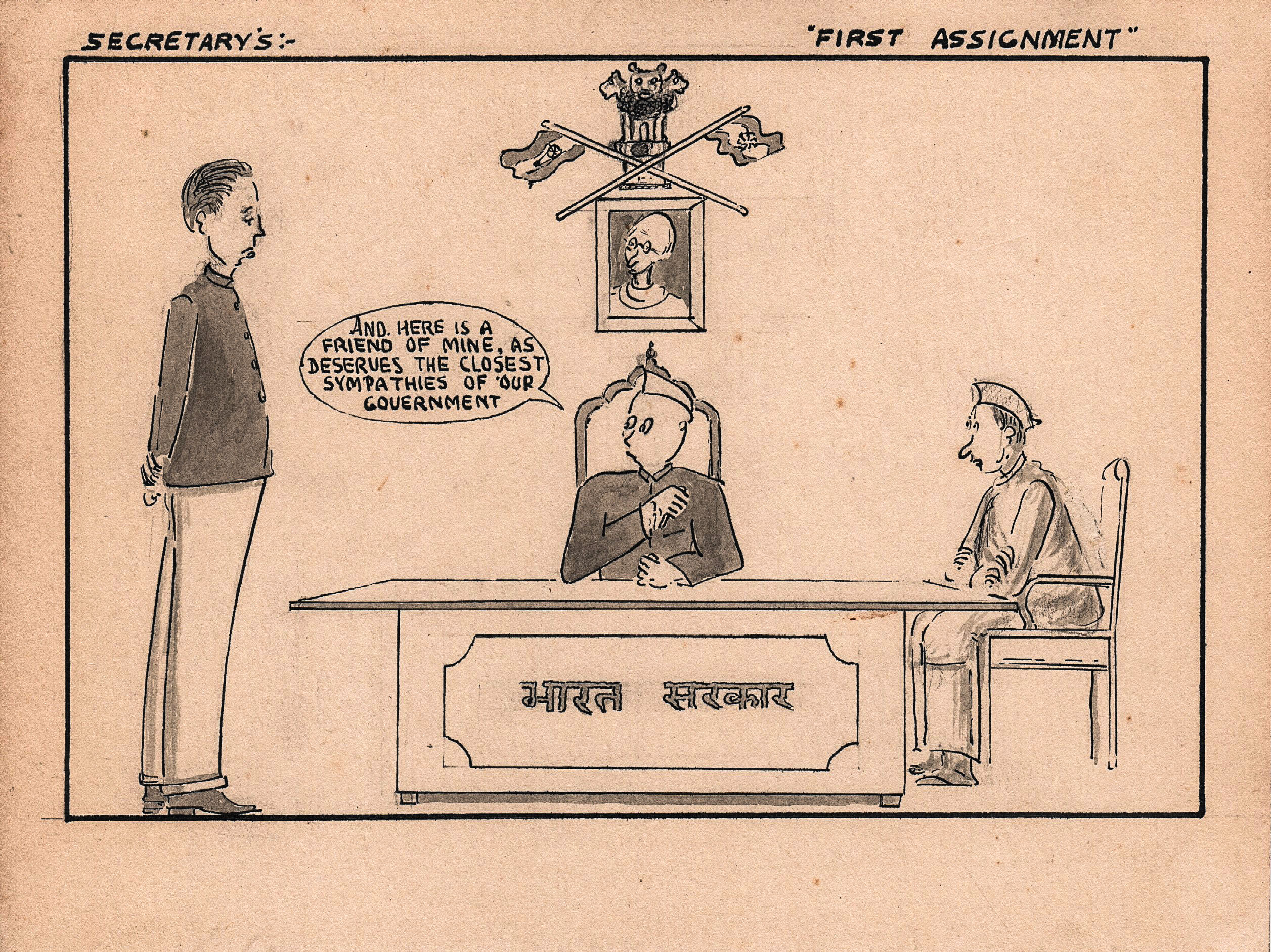

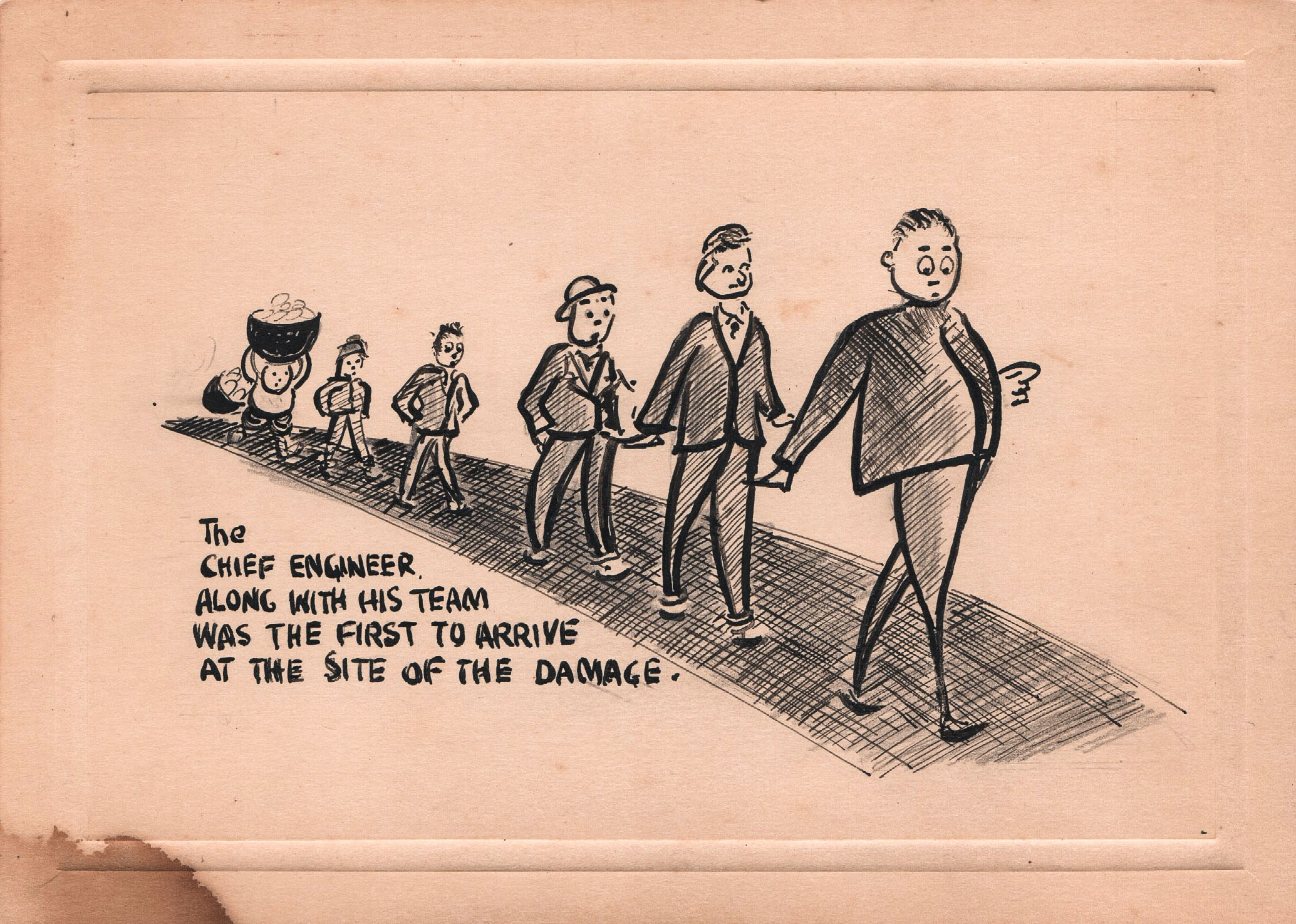

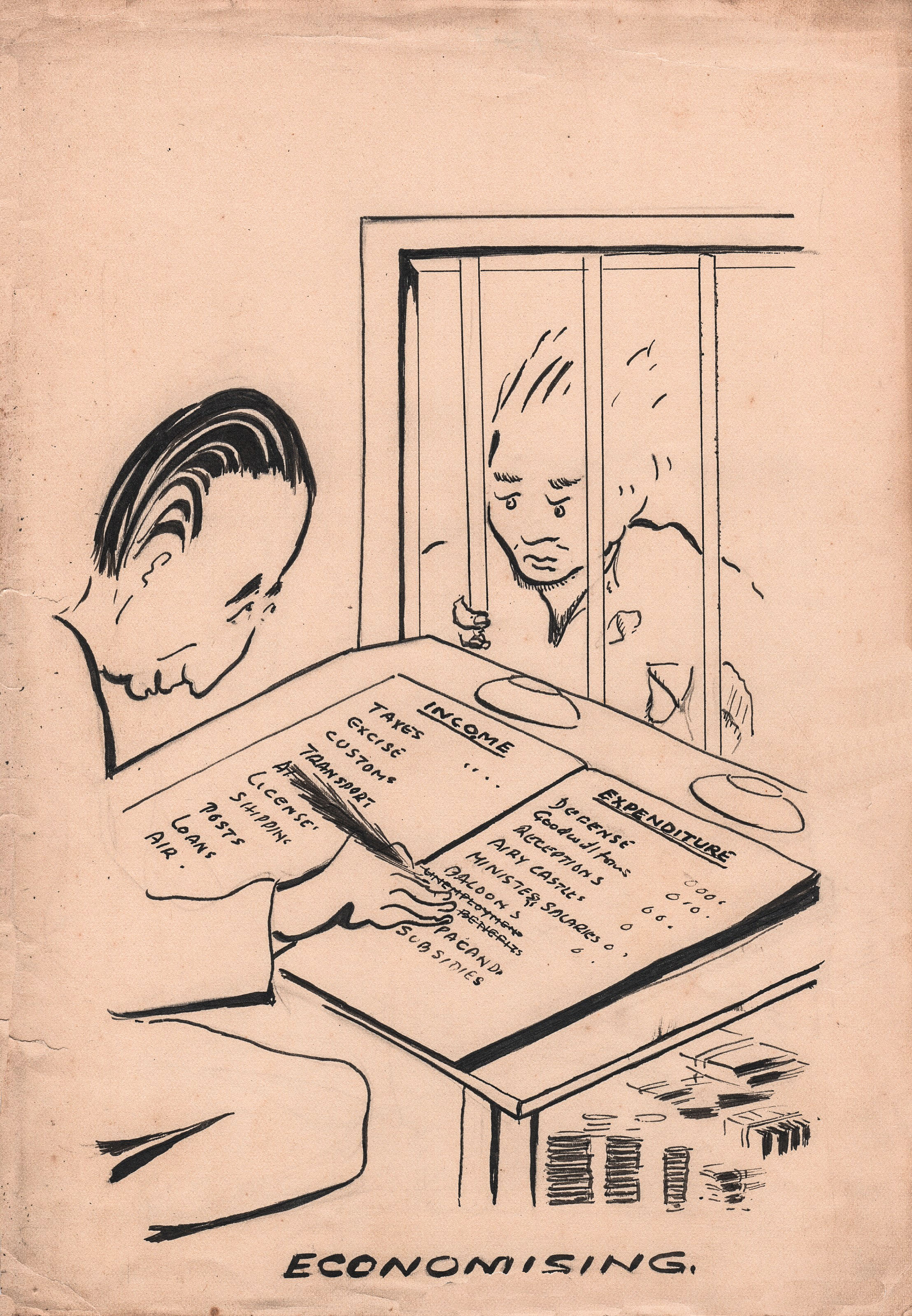

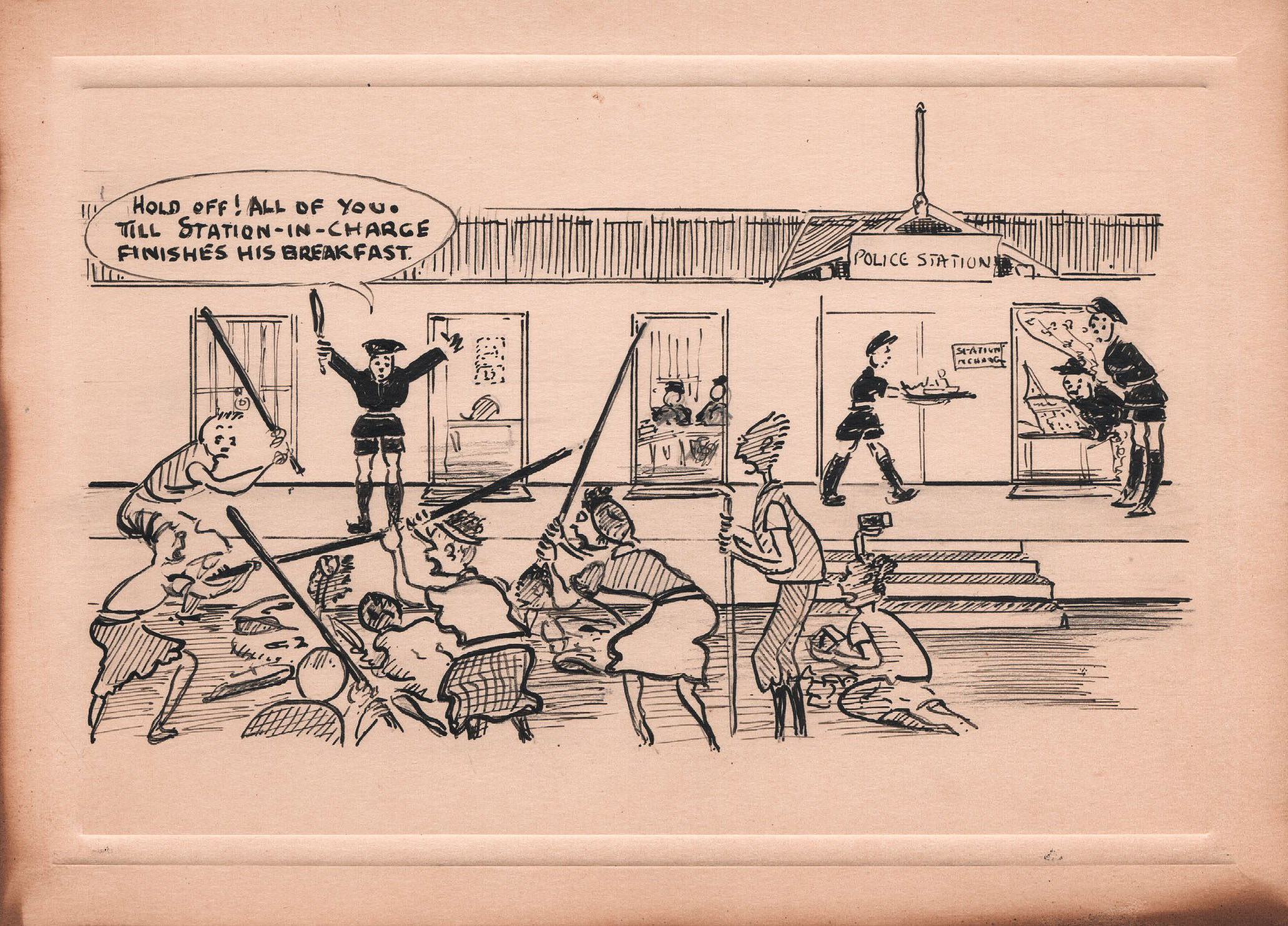

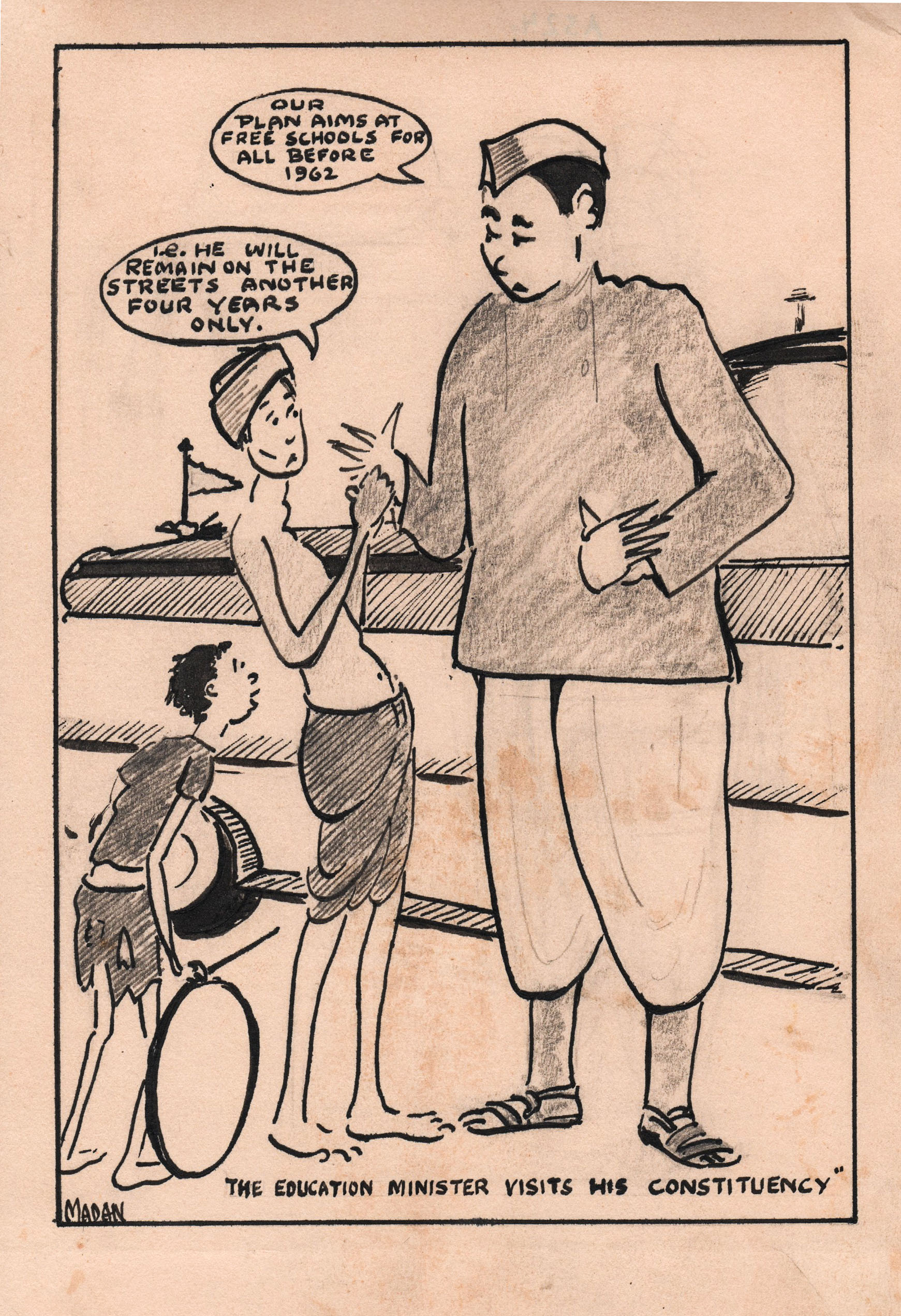

The cartoons from Phase I introduce us to Inder Bhan Madan’s sharp political commentary stemming from his pointed observations on the growing pains of young modern India. His remarkable absorption of political issues and their societal consequences finds translation in his early works made using black ink and markers. Rife with variations in page size and format, this phase contains cartoons drawn in columns of vertical strip-like formats and also ones that dawdle across the page with horizontal compositions. Often consisting of multiple characters and alignments, spanning different locations and contexts, the cartoons play with composition as well as penmanship.

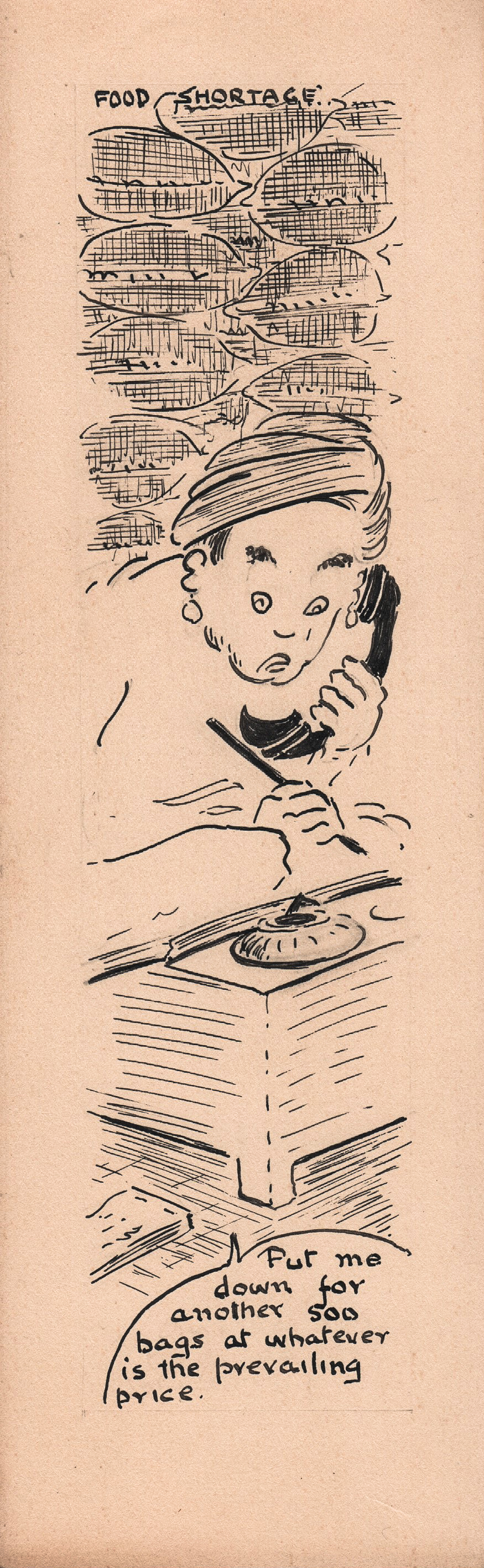

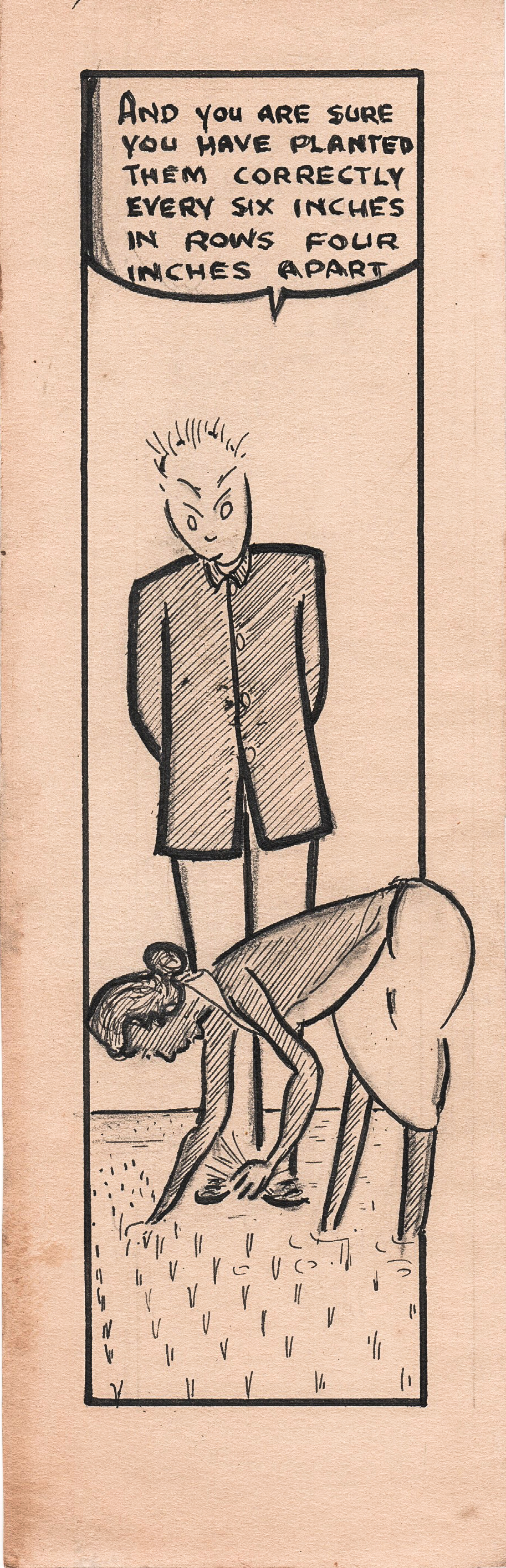

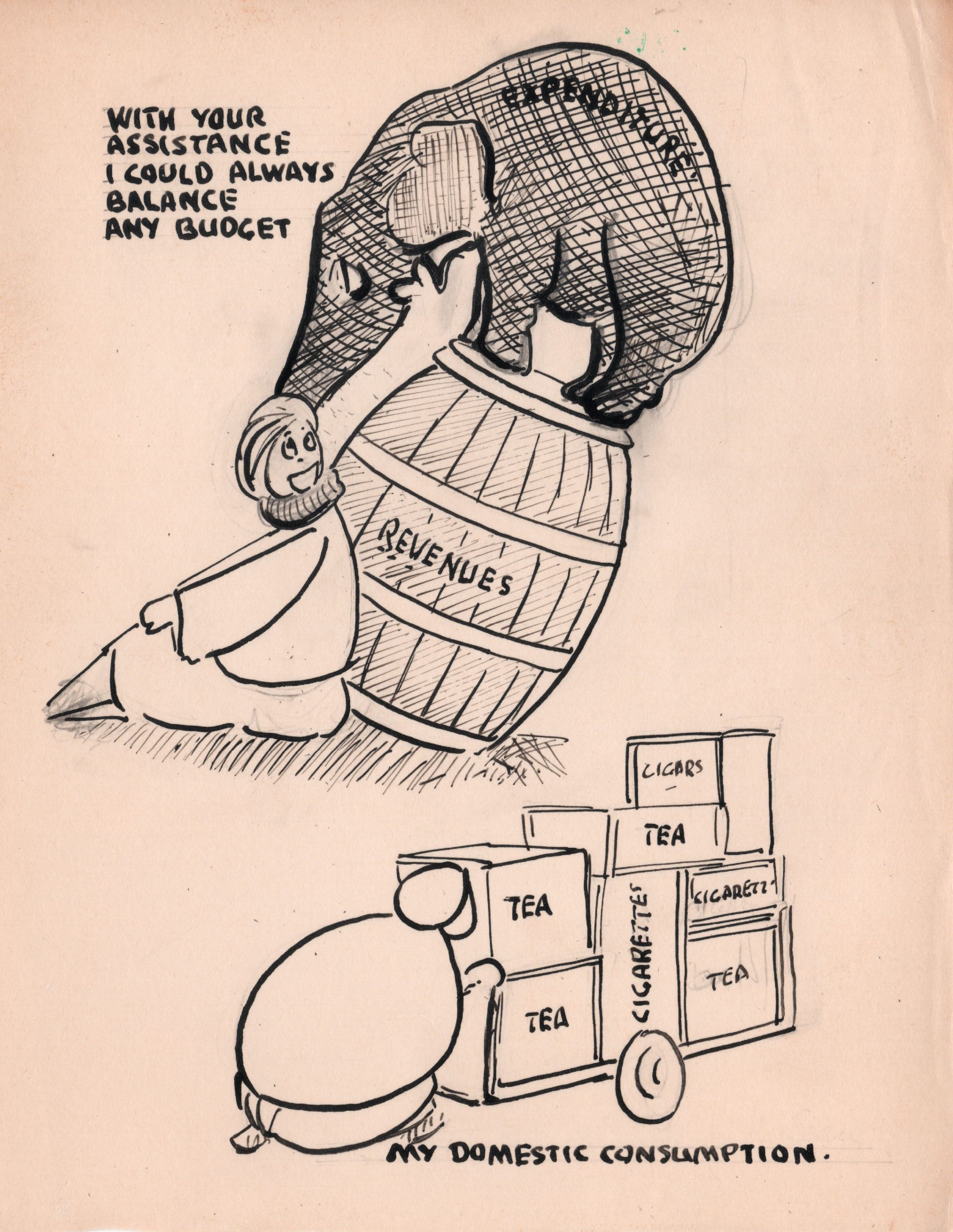

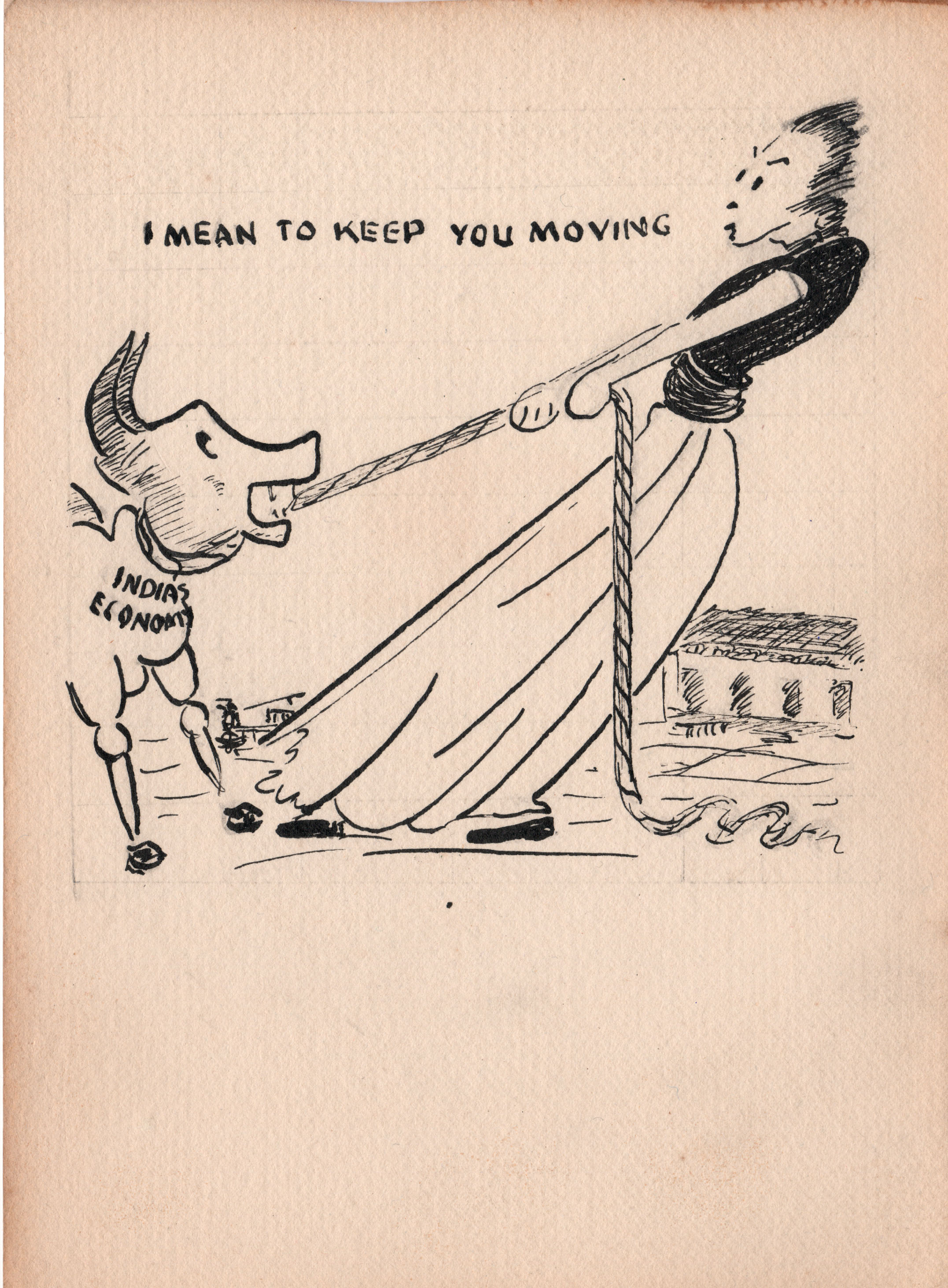

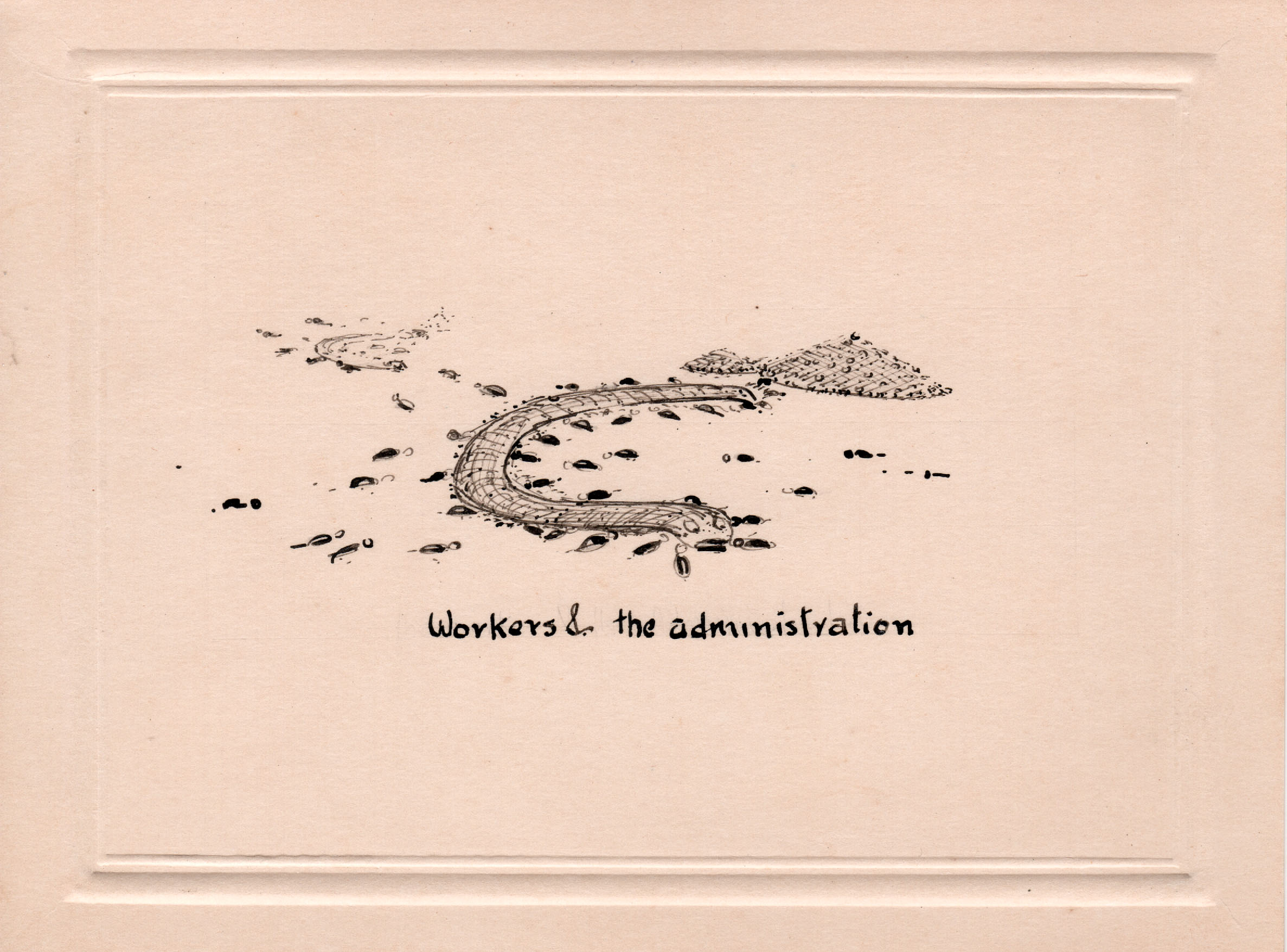

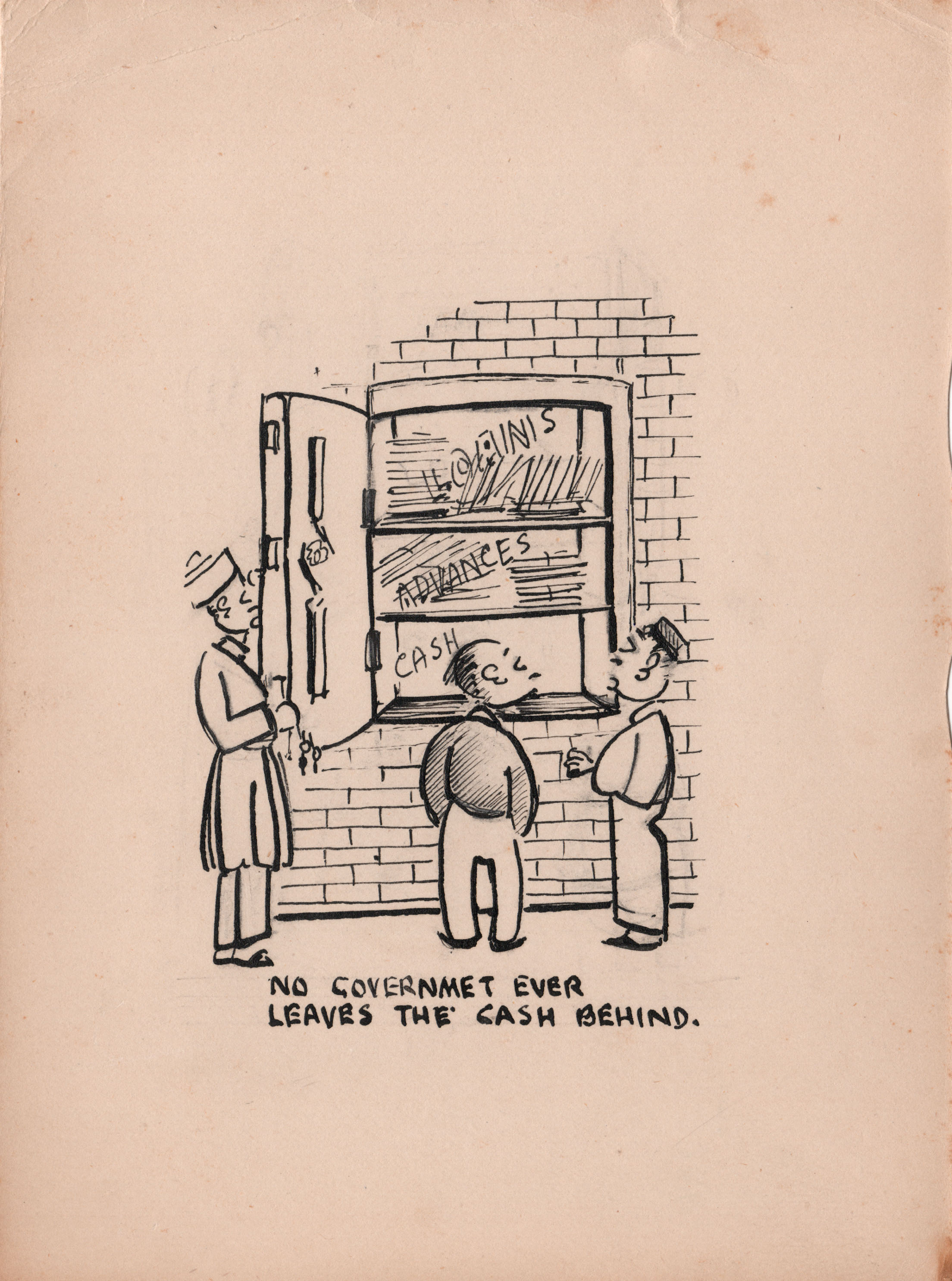

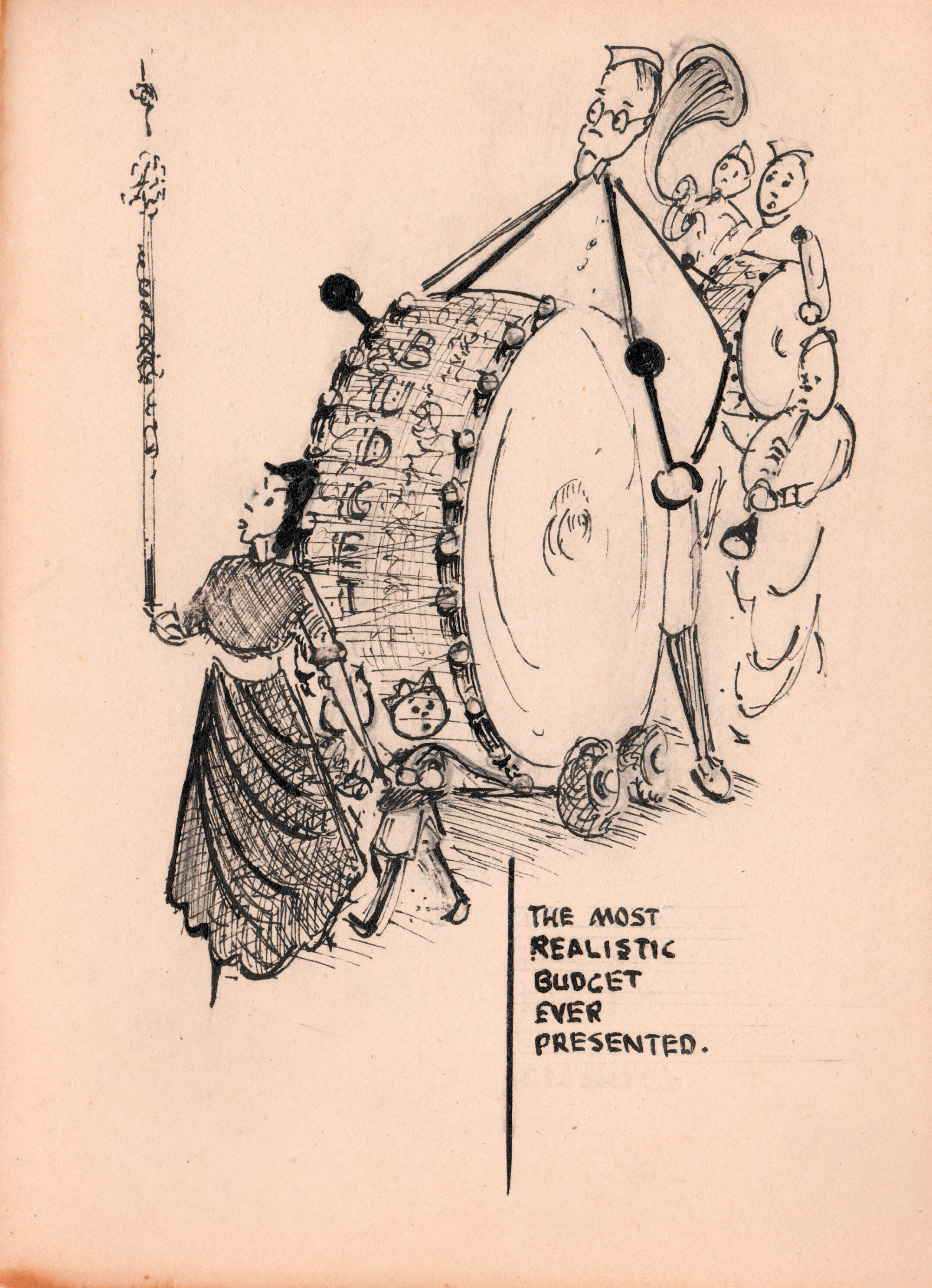

Themes such as India’s post-independence economy, development agenda, industrial growth, and government undertakings like the five year plans feature prominently here. Famines, issues of national budget and revenue as well as cow slaughter are referenced through satirical takes on current affairs. He also articulates recurring questions on the interrelationship of development and class divisions in society, bringing to light topics such as the matter of jobs and vacancies, the vacuity of election promises, the everydayness of education and issues of religion.

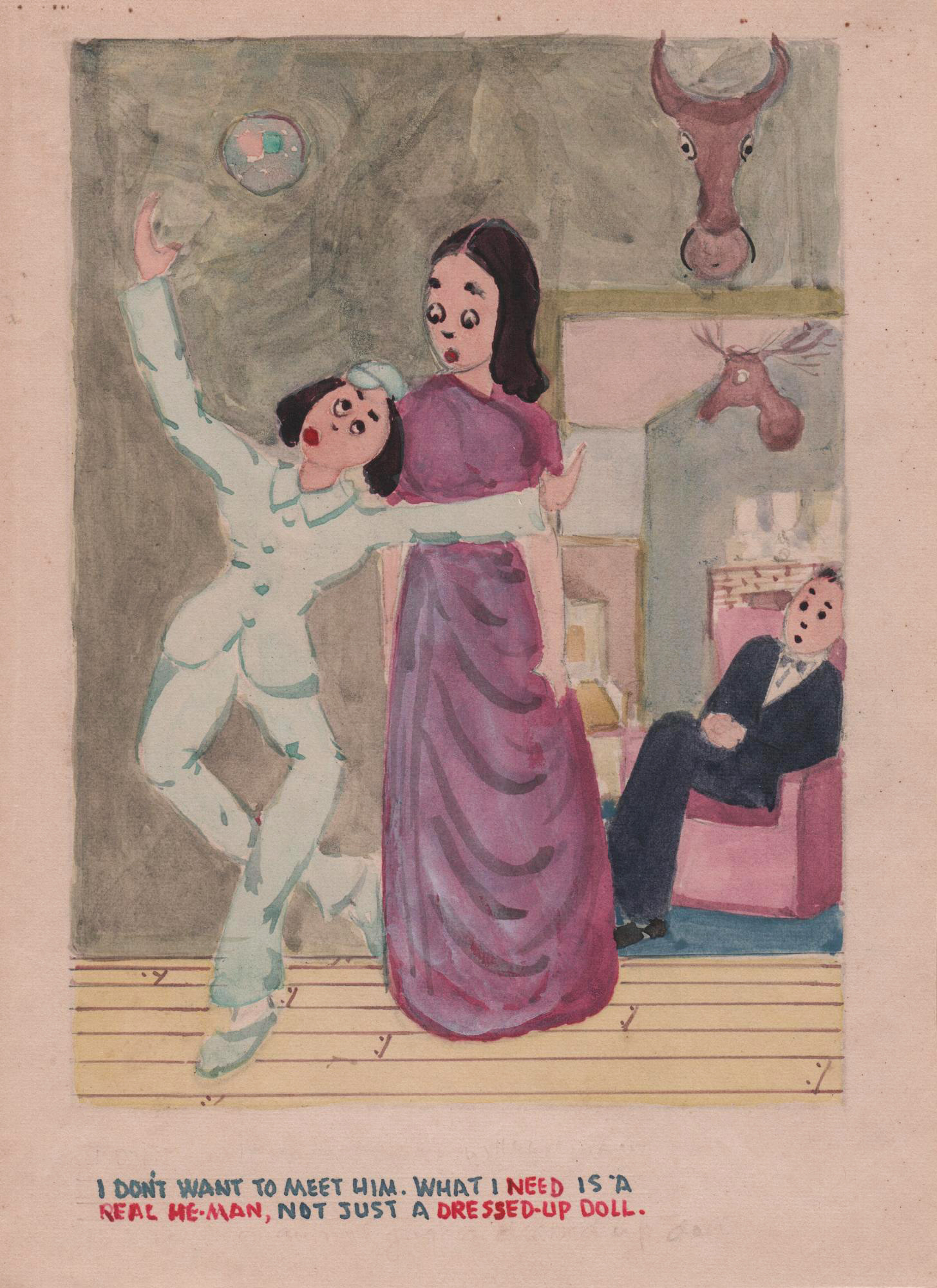

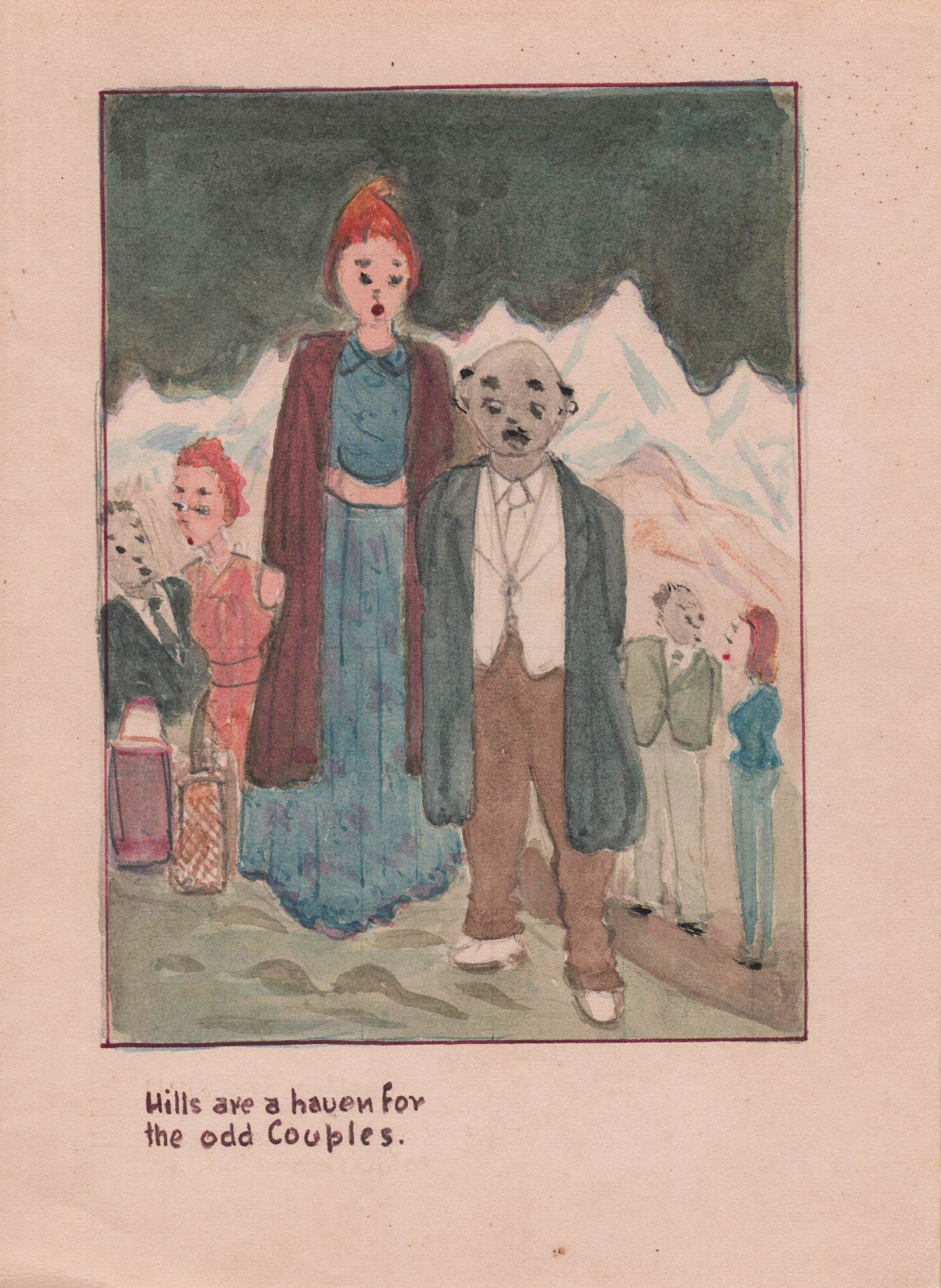

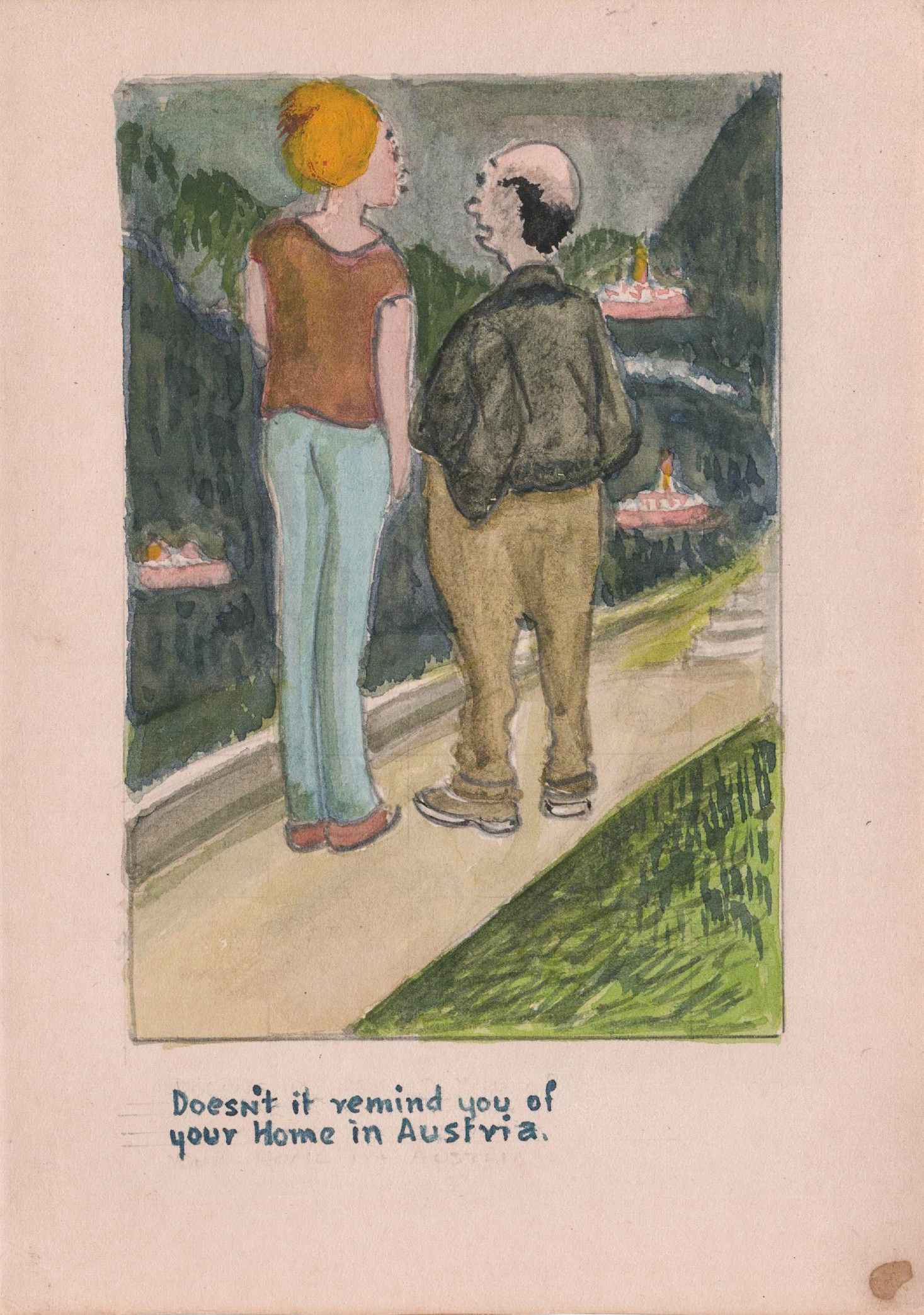

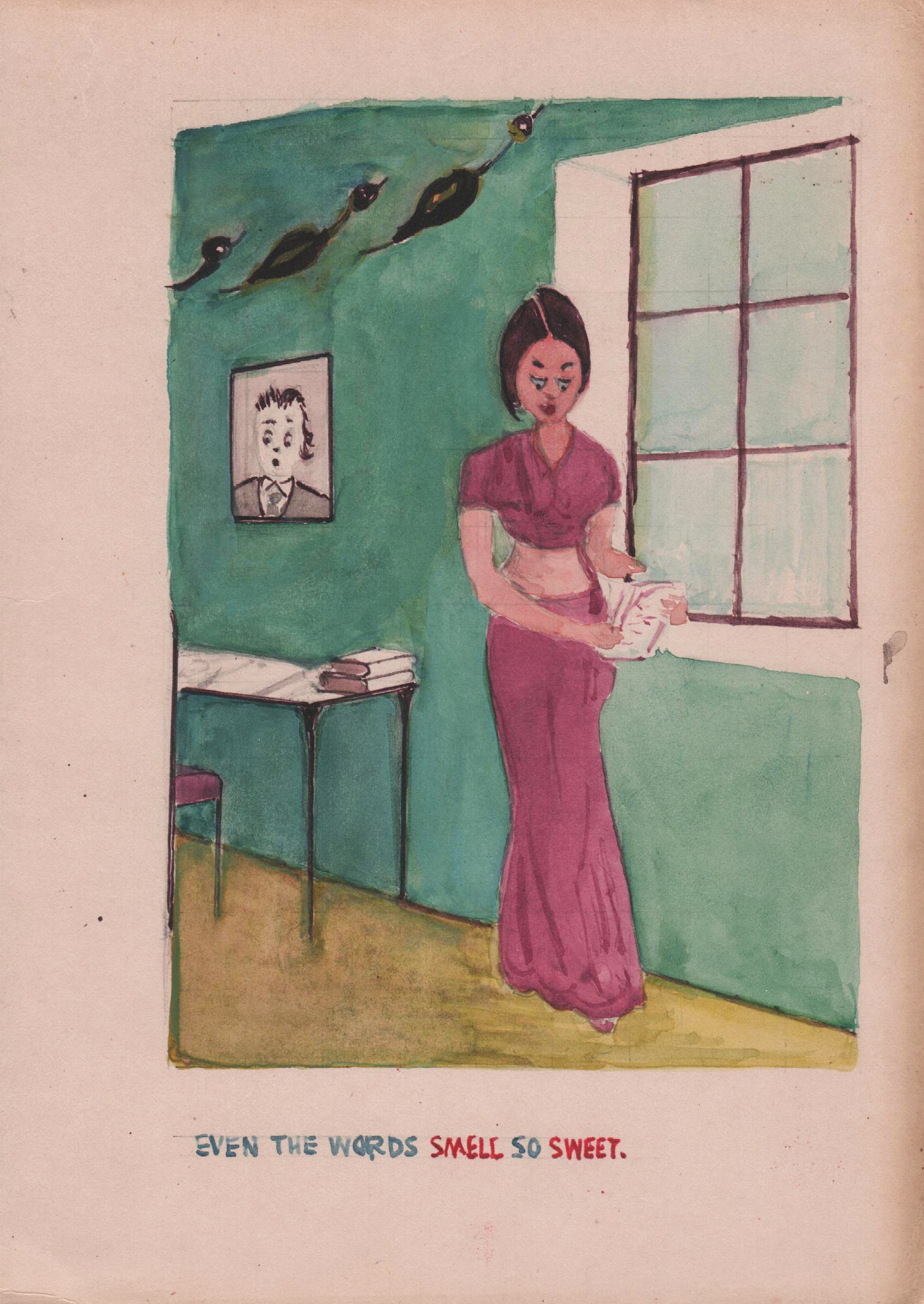

In these phases, Madan illustrates the scenes for many of the cartoons by depicting the outdoors and its different landscapes with a very luminous aesthetic. Space—as something cohabited and partaken in—is presented as an entanglement, showing layers of loneliness, activity, intimacy, curiosity, care and sentimentality. He views the scaffoldings of relationships as a lens into society and sociality, humoring us with his commentary on the intricacies of love, both platonic and romantic. With a certain light-hearted absurdity in his pairing of text and image, the cartoons here are a charming, more fluid expansion of his existing style of humorous observation.

With Phase II and III, we are introduced to Inder Bhan Madan’s readings of the domestic world, where he begins to focus more on rendering the dynamics of shared endearments, manifesting in and as scenes from interpersonal relationships. Across these two phases, we see remarkable shifts in form and style: first, a complete switch to color is made evident, and second, we are able to trace subtle changes from the vibrant hues of Phase II to a muted, sedate palette in Phase III with more dilutions in color.

Some of Madan’s finest cartoons are portrayals that depict war and its many battlefields from China to Vietnam, following vocabularies of conquest and the mundanities of frontier life. Deputed to Dibrugarh from the Post and Telegraph Department during the Indo-China War in 1962, he translated his witnessing and experience into many of his cartoons at the time.

The visual of the public demonstration is a salient element in this phase with several cartoons tracing the nature of protests, the demands of several publics and the kinds of issues that were being contested at various fronts. The recurring iconism of the banner held aloft is immediately noticeable and well-represented by Madan’s unfailingly incisive pen.

Phases IV and V contain the last years in Inder Bhan Madan’s archive of cartoons. We see a transition from the previous sections as we move into single-character portraits that retain his observational texture, supplemented by his usual lines of text. These lines appear to be his own thoughts, overheard phrases and stray conversations, placed out of context, almost like slices of his reality merging with his fictive imagination. Across both these phases, the portraits encourage us to read and interpret freely with their quick, free strokes and fluid features. The text is invitational, serving to be a rich stimulus for the imagination; what remains undoubtedly striking is the more-than-illustrative tendency of these caricatures that extends beyond the representational into universes full of stand-alone details themselves.

Derisive towards complacency and the boorishness of the bureaucracy, Madan often highlights the incorrigible figure of the politician and the bureaucrat—recurring characters, contrasted by the often agitated, anxious and comically resigned voice of the common citizen.